The problem

“Even a well-maintained septic tank in a poorly located area pollutes the environment. About 220 septics drain directly into the Kingston catchment, which feeds into our bays. With an average of 2.2 persons per household and an average water consumption of 140 litres per person per day, this means around 67,800 litres of untreated effluent is entering the Kingston catchment groundwater, every day.”

A year ago, on the night of 30–31 July, Norfolk Island experienced a downpour with 83 mm falling overnight. The flood of water entering Emily Bay that day was heavily polluted – sadly, a difficult and somewhat unpalatable truth. For me, that downpour started a chain of events that led to my creating this website so I could highlight the beauty of Norfolk Island’s lagoon habitats – and what we stand to lose if events like this are not prevented from happening in the future.

Although that downpour was detrimental to the lagoons’ environment, I firmly believe in accentuating the positives. Our coral reef is unique and beautiful. And it deserves to be looked after.

According to a Norfolk Island Regional Council’s (NIRC) Facebook post on 2 August 2020 and in a media release on 3 August 2020, issued after that rain event, the count for thermotolerant coliforms (also called faecal coliforms) entering Emily Bay was greater than 1,000,000 CFU/100 mL (more than 6,500 times the acceptable limit). To put that in perspective, according to NDTV on 26 May 2019, the highest faecal coliform count in the River Ganges was found at Khagra in Berhampore in West Bengal where it was 30,000 MPN/mL (one MPN is equivalent and interchangeable with one CFU), which is twelve times greater the permissible limit and sixty times greater than the desired limit (in West Bengal).

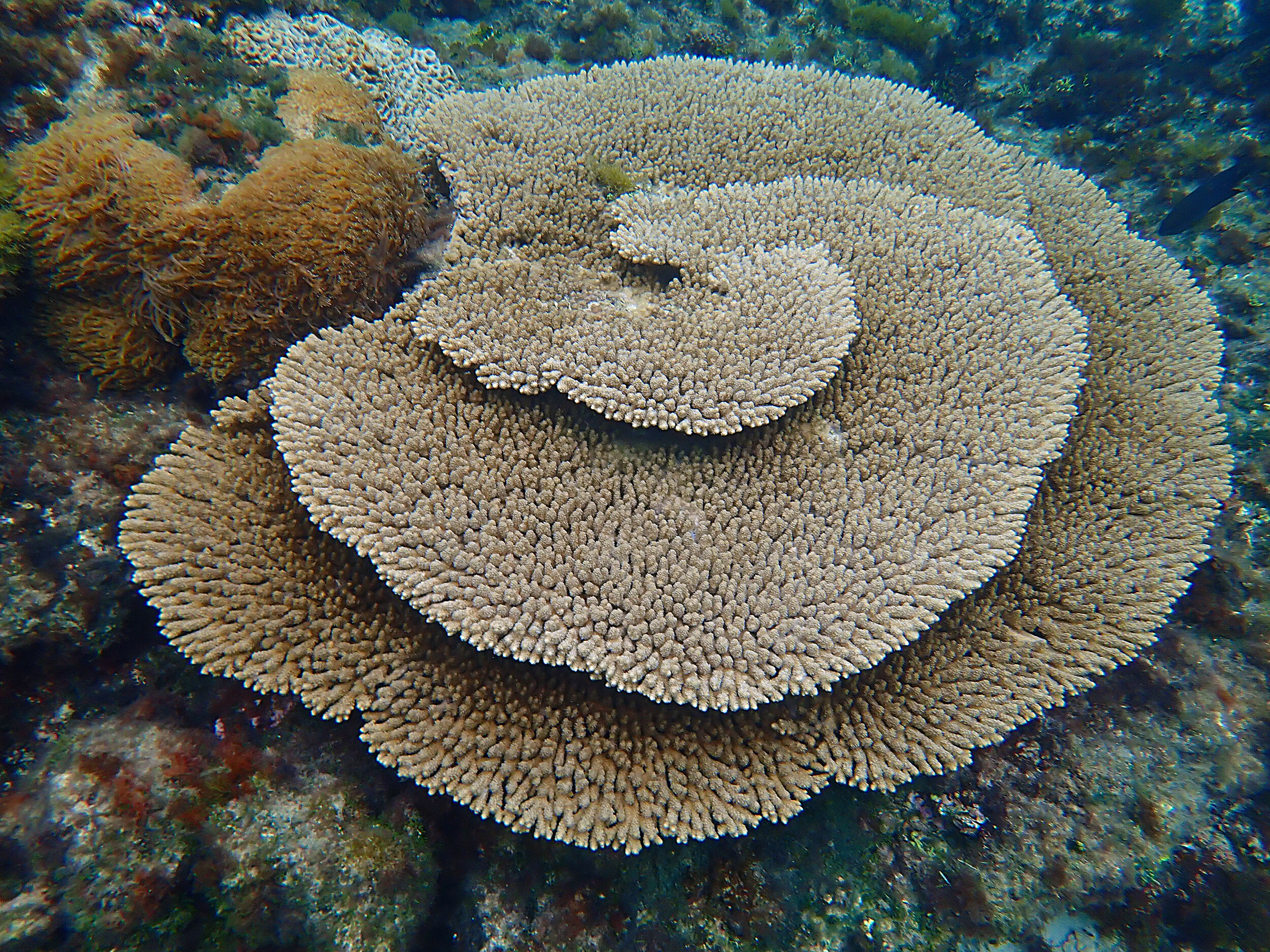

Taken on 5 November 2020

To compare Emily Bay to the Ganges seems both heretical and improbable. But on that day, those were the readings for the water issuing from the creeks into the bay. It is a simple matter of fact. And it would be two months, on the 30 September 2020, before NIRC was able to remove the warning signs around the bay, and inform us in a media release that Emily and Slaughter Bays were once again safe to swim in.

But that wasn’t the end of it. Another heavy flood in November sent the levels skyrocketing again. Once more the signs went up; Emily Bay was not safe for swimming.

As for my non-scientific observations: I witnessed a massive increase in algal growth, fewer fish and fewer species of fish in the weeks and months after these events, and, later, increased incidences of coral disease. And the repercussions continue.

What do we know about the problem?

So how did it come to this? How did we get to the stage where the water quality entering ‘pristine’ Emily and Slaughter Bays is such that it is harming our marine ecosystem and our health?

Since at least 1966, so for 55 years, there have been warnings and disquiet about the state of the waters around Norfolk Island and, in particular, in Emily and Slaughter Bays, both from a health perspective and out of concern for the unique marine habitat. Many people have put their hands up to alert those in power about what needs to be done. I know your names, and I salute you for coming forward. I do understand why the issue was kicked like a can down the road. Money, or rather lack of it, being the major obstacle.

Over the last fifteen years or so there have been multiple reports on the water quality issue, commissioned by a variety of different government departments, administrations, or bodies, including these:

Norfolk Island Hydrology Study (Diatloff, 2007)

Assessment of Groundwater Contamination in the Built-up Areas of Norfolk Island (Wilson 2010)

Water Distribution System Integrity Investigation Study: Government House, Norfolk Island (Diatloff, 2011)

Norfolk Island Water Quality Study: Emily Bay and Upper Cascade Creek Catchments (URS 2013)

Norfolk Island Water Quality and Sewerage Infrastructure Management Strategy (2014)

Emily Bay and Upper Cascade Creeks Catchments: Norfolk Island Water Quality Study (AECOM 2017).

A report prepared for NIRC in 2017 titled ‘Water quality in the KAVHA Catchment’ summarised these, as follows:

The aforementioned studies have consistently identified elevated levels of microbial contamination and excessive nutrient loads in the lower waterways flowing through the Kingston Commons, Town Creek and the Recreation Reserves. E.coli levels reported in the waterways which discharge into Emily Bay have been shown in numerous studies to almost always exceed safe levels for primary contact, swimming and fishing. These waters were only considered suitable for restricted uses where human contact was avoided.

Since then, there have been further reports commissioned and delivered:

Upgrade of Norfolk Island’s Sewerage Treatment Plant, Balmoral Group, for NIRC (2019)

Improving the water quality of Emily Bay, Norfolk Island, Bligh Tanner, for Australian Marine Parks (2020).

And we are currently waiting on the final report from Sydney Institute of Marine Science – on behalf of Australian Marine Parks – to be released, titled ‘Norfolk Island Lagoonal Reef Ecosystem Health Assessment 2020–2021’, which I suspect will concur with all the above.

More recently, on the weekend of 24 July 2021, NIRC placed two media releases in the local Norfolk Islander newspaper. One, called ‘Water Quality Improvements’, said this:

A number of studies over recent years have shown that water quality issues in the KAVHA [Kingston] catchment (Watermill and Town Creeks) are having an impact on marine waters and the coral reef within Emily and Slaughter Bays through increased nutrient loads and sediment. This issue is in addition to ensuring that our beaches and marine waters are safe for humans to use and swim in.

In the other media release, titled ‘Proposed Update to the Water Resources Development Control Plan’, this:

The impact of human activity on the island, in particular, poorly placed and managed septic tanks is known to have a detrimental impact on the receiving environment [the Marine Park around the island]. The high nutrient loads from soakage trenches and livestock is now severely degrading the reef in Emily Bay which is showing signs of significant coral death and algae growth.

So it isn’t like we don’t know what is happening.

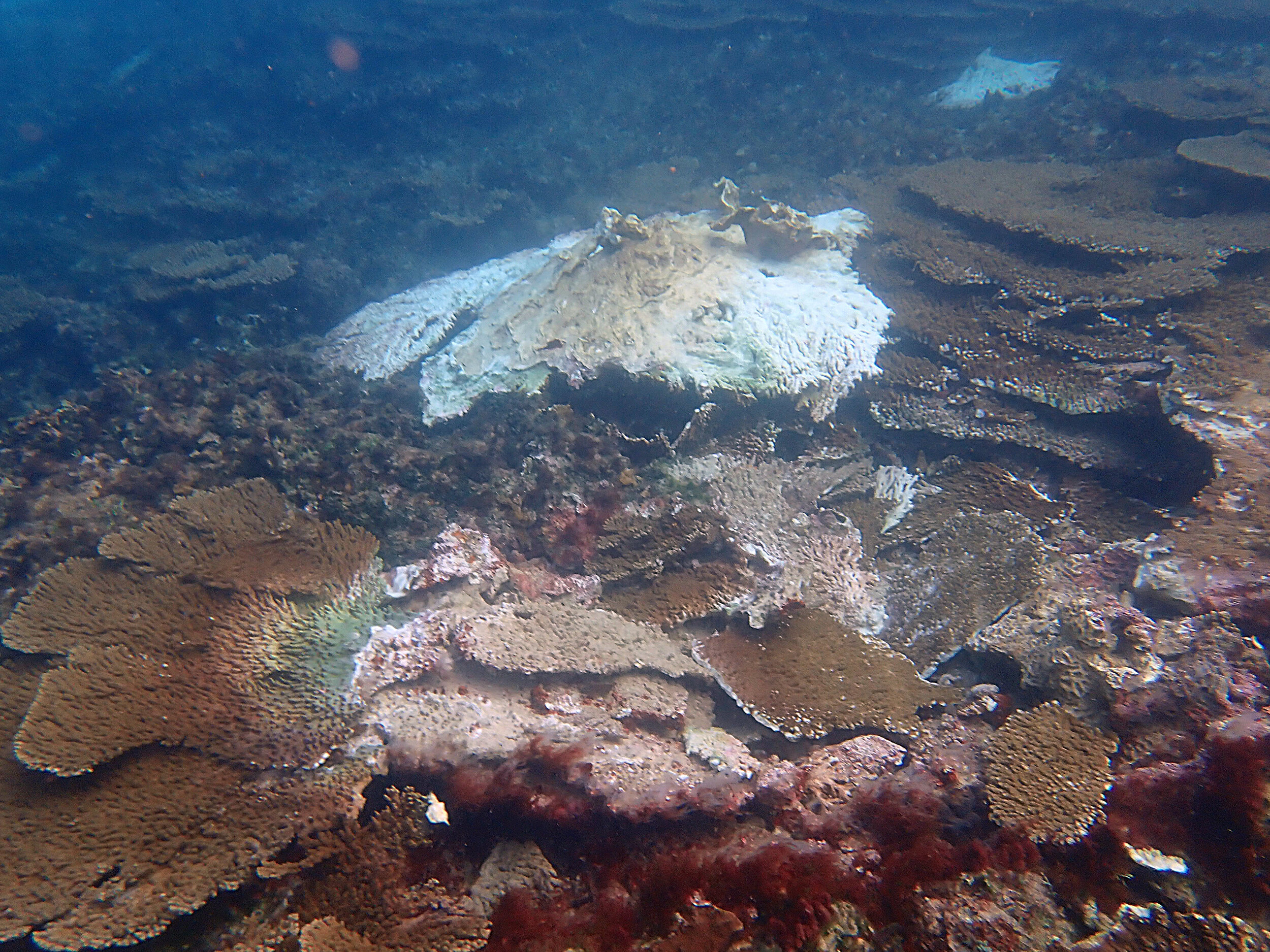

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the die-off of coral, increased algal growth, both on the floor of the bay and covering the dead coral habitat, plus the decrease in the number and diversity of small fish, has accelerated during the past ten years. And let’s not forget, all this is happening while the reef struggles with other pressures as well: in 2020 we had a widespread bleaching event; and since January 2021 we have experienced the effects of La Niña, which has led to the extensive destruction of plate corals in Emily, Slaughter and Cemetery Bays, some as old as 30 or 40 years.

It took one significant rain event, superimposed on a malfunction of a pumping station that is part of the water treatment network at the top of the hill, and a blocked pipe, to bring the issue to a head. No longer can we ignore the plethora of reports and the unpalatable truth.

Why is it important to fix it?

Norfolk Island is home to one of the most southerly coral reefs in the world after Lord Howe Island. It is remote and isolated.

The location of Norfolk Island means that the coral reefs are supplied by spawn locally and if the coral all dies it is unlikely immigration of coral spawn will occur from Lord Howe, 900 km away, or Australia, which is even further. It would have to come from reefs around Norfolk, Nepean and Phillip Islands.

We are still discovering new species in our bays – corals, in particular. But, also, we are still identifying other rare species. I recently photographed the incredibly rare Tonna melanostoma, a giant sea snail, one of at least three species of Tonna living in our lagoons. My photographs are currently the only known images of a live animal. I have co-written a paper on this, which will be published in the October 2021 edition of Gloria Maris, a publication of the Belgian Society of Conchology.

This ecosystem is an intrinsic part of the island’s culture and heritage, and it deserves our care and protection.

And this doesn’t even begin to touch on the issue of public health: ear infections, wound infections, gastroenteritis, and more.

Without our reef, the coastal plain at Kingston will be unprotected, and will be more likely to suffer inundation from extreme high tides and storms. Kingston is an area of outstanding national and international significance. It is one of eleven historic sites that together form the Australian Convict Sites World Heritage Property.

How did we get here and what are we doing about it?

The pollution stemmed – and stems – from different sources across the catchment, all of which need tackling urgently if we are to prevent irreversible damage to the reef.

Tonna melanostroma

In the media release from the Administrator’s office of 24 July 2021, ‘Water Quality Improvements’, was this statement:

As part of the effort to improve water quality on Norfolk Island with a focus on Emily/Slaughter Bays and the Marine Park, a Water Quality Working Group has been formed amongst government bodies. NIRC, Parks Australia, the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications (DITRDC) and the Office of the Administrator are meeting on a routine basis to discuss and coordinate actions for water quality improvement. Some of these actions have already been implemented, including the installation of leaky weirs, and the installation of cattle fencing along Watermill Creek by DITRDC and Parks Australia. These measures are critical in working towards a healthy catchment. The group will also consider future activities relating to water quality

Free-roaming cattle, while culturally significant, contribute to the pollution in waterways. Fencing the common areas of Kingston, allowing vegetation to grow along the creeks, has slowed water flow and prevented cattle from entering the waterways there.

Leaky weirs (aquifer recharge) that have recently been installed in the Kingston area also prevent the water, to a point, from rushing down Watermill Creek (but not the more polluted Town Creek) and out into Emily Bay.

In addition, all the septic tanks in Kingston have been resealed and are now regularly pumped out to avoid the situation where they are draining into the environment in close proximity to the bays.

These interventions are great, as far as they go, and have improved the overland water flows into the bay. But they don’t fix the issue at the top of the hill and along the creeks. Which are as follows:

We have contaminated groundwater, principally caused by the ongoing use of septic tanks and soakage trenches. Of the approximately 1,000 tanks installed on the island, NIRC believes as many as a quarter are failing, although I have seen reports that claim as many as 50 per cent, and that most would not satisfy required setback distances from waterways and boreholes. Of these 1,000 septic tanks, about 220 are in the Kingston catchment (this does not include the ones in Kingston itself). This equates to 67,800 litres going directly into the Kingston catchment.

By their very nature, soakage trenches are designed to drain, so even a well-maintained septic tank in a poorly located area is polluting the environment. The connectivity of the aquifers means that septic systems across Norfolk Island could be contributing to the contaminated groundwater. Meaning that the 220 septics in the catchment are only the tip of the iceberg.

At the last census in 2016 there was an average of 2.2 persons per house, 1,000 houses, and an average water consumption is 140 litres per person per day. This equates to approximately 308,000 litres of untreated effluent entering the environment daily. More than double the volume collected by the water treatment plant.

CSIRO have recently completed the Norfolk Island Water Resource Assessment, where the brief was, as the report’s title suggests, to examine the island’s water resources. On 17 June 2021, the Office of the Administrator on-island issued a media release that said this:

Following my announcement last month about the Australian Government’s funding for the continuation of CSIRO’s Norfolk Island Water Resources Assessment (NIWRA) project, I am pleased to confirm the project’s expansion to include water quality investigation.

…

The Australian Government is committed to working with stakeholders including the Norfolk Island community to help improve water quality. Under the ongoing water project, the Australian Government is funding the CSIRO to:

expand the NIWRA monitoring program to include water quality data collection, monitoring, analysis and evaluation, in collaboration with Parks Australia and Norfolk Island Regional Council.

undertake targeted water quality studies to improve the understanding of potential risks to marine water quality and inform development of catchment management innovations

I applaud this initiative. In broad terms, CSIRO will be looking deeper into the contamination of the water table and how this affects the bays. The groundwater, or aquifer, comes to the surface in the bays, ergo so too does the contaminated water. One of my observations has been the amount of algal growth in Slaughter Bay, supposedly the cleaner of the two bays after a heavy rain event (when overland water nromally only discharges into Emily Bay) principally because it gets flushed more readily by the ocean currents. I could never square what I was seeing with my eyes and this information, so I will be interested to see CSIRO’s next report. However, the concern I have is that as we wait for yet another report to tell us what we can see with our eyes, the reef continues to deteriorate.

The current condition of the sewerage treatment plant is deemed to be poor and at high risk of failure within the next five years (according to a NIRC-commissioned report from the Balmoral Group Australia in October 2019 called ‘Upgrade of Norfolk Island’s Sewerage Treatment Plant’). The report says, ‘Immediate action is required to manage the discharge of effluent and sludge into the Marine Park, which is prohibited under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Act (EPBC) …’

Importantly, the effluent currently coming out after treatment, which is sent over Headstone and into the Marine Park, albeit around the corner from the lagoons, is of poor quality and only marginally better than the raw waste that goes in.

It was a malfunction of one of the pumping stations to this treatment plant that saw highly polluted water cascading down the creek and into Emily Bay on the night of 30 July 2020.

NIRC is very aware of this problem, and that it may be subject to fines as high as $9 million by failing to fulfil the requirements of Parks Australia as outlined in the Temperate East Marine Parks Network Management Plan 2018, which is to protect biodiversity and other natural, and cultural and heritage values of marine parks in the Temperate East Network. However, NIRC is not in a position to foot the bill for this urgent piece of infrastructure, which last I heard is anticipated to cost about $17 million to fix.

Where to from here?

I would like to acknowledge my appreciation for the measures that have been taken so far, and also to all the hard work put in by staff working for the different government stakeholders. However, I will also add that the really big-ticket items still need to be addressed as a matter of some urgency, including: the island’s outdated water treatment plant; connecting more houses to this system (Longridge and Little Cutters Corn); and addressing the issue of private septic systems that are run down and badly maintained, and in all likelihood not fit for purpose, which are contaminating the island’s groundwater and, ultimately, the bays at Kingston. This last item worries me the most, as I know that private individuals are going to find it very difficult to raise the money to update their systems. I wonder if consideration could be given to buying a new generation of septic systems in bulk in order to obtain a discount, or to offering interest-free loans, for example.

I have repeatedly brought these matters to the attention of the Hon Assistant Minister Nola Marino and others. One response from her office, dated 10 December 2020, said this:

‘Parks Australia is responsible for water quality in the Norfolk Island Marine Park.’

Really? Surely what goes into the Marine Park is the responsibility of the Norfolk Island Regional Council (which is just about bankrupt) and the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications?

I wrote again on 25 July to register my concern about the lack of action on what I referred to as the ‘big ticket items’ that still need to be addressed. In her response, dated 19 August, among other things, Ms Marino referred to the CSIRO research that is now being undertaken (as I have mentioned, above). Meanwhile any action on cleaning up our act is delayed further while we wait for CSIRO to do their research and release their findings.

This really is a wicked problem that crosses many jurisdictions and involves many stakeholders. I realise that fixing these things is never straightforward, nor as easy as community members would like to believe. We need to put aside the silo mentality that blames other jurisdictions for problems and stop congratulating ourselves over fixing the low-hanging fruit and sort out with some urgency our wastewater management issues. Norfolk Island is not part of a third-world country. Coral reefs are precious. Let’s find some effective and constructive solutions to ensure the health of our reef and the safety of our swimming beaches by working together.

I am hopeful that soon, and I mean very soon, we will have a solution so that Norfolk Island’s beautiful reef can get back to healing and growing. It is an important part of our tourism offering. I am no environmental economist, but I would still wager that fixing the problem would be cheaper in the long run.

After 55 years of warnings and alarm bells it is time for some decisive action. The time for reports and obfuscation has passed. We know exactly what the problem is, now we just have to fix it.

Slaughter Bay with extensive algal growth on the coral, April 2021

Edit: 4 September 2021

Below are the two finalised reports spelling out the water-quality issues around Norfolk Island’s reef.